What is Impostor Syndrome? Learn How to OWN YOUR GREATNESS

- Book Sample /

- Self-Help

Impostor syndrome is an overwhelmingly common phenomenon. Did you know that up to 70% of people in the world may experience feelings of impostor syndrome? If you have ever felt like a fraud, or as though you don’t deserve the success you’ve achieved or life you have built, you might be experiencing impostor syndrome.

Dr. Lisa Orbe-Austin and Dr. Richard Orbe-Austin wrote Own Your Greatness: Overcome Impostor Syndrome, Beat Self-Doubt, and Succeed in Life to provide a research-backed program to help you overcome impostor syndrome through a series of interactive exercises. Below is an excerpt adapted from chapter 1 of the book that goes over the definition of impostor syndrome and how it can show up for different people.

For more information and access to the complete program, check out Own Your Greatness, on sale today!

An Overview and Assessment of Impostor Syndrome

In the 1970s, two psychologists, Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes, were working in the college counseling center at Georgia State University when they first observed this phenomenon in the women that they were treating. Drs. Clance and Imes noticed that they were working with very outwardly accomplished women, both students and faculty, who felt that they had acquired these credentials and opportunities in a fraudulent manner, and that at any moment they could be found out. They wrote a paper in 1978, coining the term “impostor phenomenon.”

In the 1970s, two psychologists, Pauline R. Clance and Suzanne A. Imes, were working in the college counseling center at Georgia State University when they first observed this phenomenon in the women that they were treating. Drs. Clance and Imes noticed that they were working with very outwardly accomplished women, both students and faculty, who felt that they had acquired these credentials and opportunities in a fraudulent manner, and that at any moment they could be found out. They wrote a paper in 1978, coining the term “impostor phenomenon.”

Impostor syndrome is the experience of constantly feeling like a fraud, downplaying one’s accomplishments, and always being concerned about being exposed as incompetent or incapable. As a result, people with impostor syndrome engage in either overworking or self-sabotage. Impostor syndrome affects high-achieving professionals who are seemingly successful. However, when experiencing impostor syndrome, you are unable to enjoy your success and believe that this success is precarious.

Research indicates that 70 percent of all people have experienced the Impostor Phenomenon at some point in their lives. This syndrome can feed feelings of anxiety, low self-esteem, depression, and frustration due to the thoughts and behaviors that result.

Signs of Impostor Syndrome

Here are the signs that you may be struggling with impostor syndrome. Perhaps you:

- are high achieving.

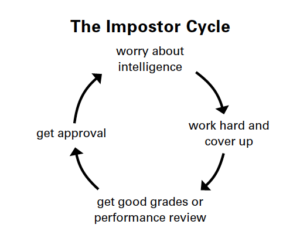

- engage in The Impostor Cycle.

- desire to be “special” or “the best.”

- deny ability and attribute success to luck, mistake, overwork, or a result of a relationship.

- discount praise, feeling fear and guilt about success.

- fear failure and being discovered as a fraud.

- do not feel intelligent.

- have anxiety, self-esteem issues, depression, and frustration from internal standards.

- struggle with perfectionism.

- overestimate others and underestimate oneself.

- do not experience an internal feeling of success.

- overwork or self-sabotage to cover the feelings of inadequacy.

Initially, Clance and Imes thought that impostor phenomenon would be found predominantly in women because of societal stereotyping that leads women to feel that they are less competent in certain domains (e.g., math, science, leadership). However, the research has been inconsistent and often finds that it is represented equally in men and women, although the findings suggest that women and men with impostor syndrome may behave differently in response to it.

Impact on Education and Career

Clance and Imes noted that there were four particular hallmarks of impostor syndrome in the women they studied: 1) diligence and hard work; 2) intellectual inauthenticity; 3) charm and perceptiveness; 4) seeking mentorship for the purpose of external validation.

1. Diligence and Hard Work

In their seminal paper, Clance and Imes found that the women that they had observed used hard work and diligence as a cover-up for their perceived inadequacy. The women would engage in a cycle that looked like:

Receiving the praise would result in temporarily feeling good and at that point, once the good feelings subsided, they returned again to worrying about intelligence or ability to perform. Within this cycle, there is no internalization of the successful experience. The accomplishment isn’t accepted as part of their identity or attributed much value, so the next time they perform, it’s as if the previous accomplishments never existed. Thus, the cycle begins again.

In more recent research, it has been revealed that people do not only engage in hard work in that second stage but can go in the opposite direction with self-sabotage. This is most commonly seen when someone with impostor syndrome procrastinates, usually due to anxiety about performance and perfectionism, as they attempt to unveil themselves as an impostor. The belief is that the procrastination serves as a method to expose their status as an impostor, perhaps in hopes of releasing the stress and strain of it. However, they usually still perform well. But any mistake is interpreted as proof of their inadequacy due to their perfectionism, rather than as an artifact of being human, or of not giving themselves enough time to review the work.

The experience of self-sabotage can sometimes be hard to detect as it’s often connected to the performance anxiety, and this anxiety makes it difficult to tease out what has occurred. It can be seen in spontaneous and impulsive decisions to go against a plan, trouble organizing for high-stress events, or other subtle behaviors that affect preparedness, confidence, and performance.

2. Intellectual Inauthenticity

The second characteristic of impostor syndrome that Clance and Imes illustrated is intellectual inauthenticity, or the downplaying of knowledge, skills, or abilities, or not revealing true opinions of a situation in order to protect someone else’s feelings or preserve the relationship. When someone with impostor syndrome behaves like this, it only furthers their belief that they have engaged in some form of deception, exacerbating the feelings of being fraudulent. The kind of relationships that this intellectual inauthenticity might preserve are those with people who demonstrate narcissistic characteristics (e.g., needing excessive praise and not being able to tolerate critique or dissent) and/or have a fragile sense of themselves and their accomplishments. These can be dangerous people for those with impostor syndrome to connect with. You can see this as illustrated in Elise’s ongoing experience at the company where she has been a longtime employee:

Elise has been an office administrator at the same institution for 25 years. She has watched leaders come and go and has a significant level of understanding of the company’s history as well as an unusual expertise in the subject matter, for her position, because she has been so intimately involved in the company’s evolution. Every time another CEO is hired—and there have been many—she struggles to share her content and cultural knowledge because she senses their fragility and notices their desire to be the most knowledgeable person in the room, even though they are brand-new. In each experience with a new CEO, she becomes terrified that she will be fired because she will be seen as incompetent and outdated in her knowledge and skills.

3. Charm and Perceptiveness

Intellectual inauthenticity is often combined with a third behavior, which is utilizing charm and perceptiveness. In their ability to get people to like them and potentially advocate for them, those with impostor syndrome can feel like their ability to fool people extends beyond their intellectual capacity.

People with impostor syndrome can also exhibit high emotional intelligence. They are particularly keen at understanding what others need to make them feel valued and connected to them. They may utilize these skills, especially with mentors and senior leaders to generate positive evaluations of their behavior. However, a mentor who is not benevolent, and perhaps narcissistic as mentioned earlier, may exploit their yearning for connection and praise to maximize their performance. The potential for a truly dysfunctional relationship is highly likely in these cases. The person with impostor syndrome can find themselves in a situation where the mentor or supervisor makes them feel like they ARE truly an impostor and must constantly and unendingly prove themselves. These types of relationships become very hard to break because the person with impostor syndrome may feel as if their ineptitude has been found out, so they continually seek some sort of validation from someone who will never or very rarely provide it, because it keeps the person with impostor syndrome working hard for them.

4. Seeking Mentorship for the Purpose of External Validation

The final behavior that maintains the impostor syndrome is seeking a mentoring relationship from someone, who is well respected in their field, industry, school, or office, in order to gain external validation. But this relationship may be fraught for the person with impostor syndrome for the reason discussed above, or because it can feel inauthentic if the person with impostor syndrome believes they charmed the mentor into positive feedback because they think it has been acquired through duplicitous means (e.g., through charm).

In addition, it has been shown that people struggling with impostor syndrome have lower levels of job and career satisfaction, yet higher levels of organizational commitment. So, while people with impostor syndrome tend to be more unhappy in their jobs and careers, they are also likely to commit to these places that are making them unhappy, perhaps in an effort to create some sense of stability and predictability in terms of evaluation. Further, the research also indicates that people with impostor syndrome struggle with marketing themselves, which is critical for job searching or networking. Therefore, their salaries and promotions are usually negatively impacted, which can be seen in lower salaries and fewer promotions. It also shows up in being less optimistic about their career and being less adaptable when things go wrong. Moreover, those with impostor syndrome are likely to have a reduced knowledge of the job market, which makes taking a leap to a new role when they are unhappy even more difficult.

Throughout our experience working with impostor syndrome, we have seen it show up in the following ways that affect professional development:

- Not understanding their worth (i.e., salary comps) in the marketplace

- Fear of negotiating

- Lack of motivation to leave stagnating roles

- Reluctance to vie for promotion

- Avoidance of high-visibility stretch assignments

- Difficulty networking and communicating their accomplishments to others

- Trouble envisioning their long-term career future

All of these behaviors of impostor syndrome have a significant impact on advancement, salary, and long-term earnings, but they can be reversed.

—

Looking for more? If you’re searching for a way to finally overcome impostor syndrome and take ownership of your life and your success, check out Own Your Greatness, on sale today, or Drs. Lisa and Rich on their website and Instagram (Dr. Lisa and Dr. Rich).

Own Your Greatness

Stop letting impostor syndrome hold you back! This guided workbook of interactive exercises and research-backed activities will help you conquer self-doubt, realize your true worth, and enjoy your success. How many times have you thought that everyone is crushing it except you? How often have you looked at one of your accomplishments and

Learn more

Get the Ulysses Press Newsletter