Getting Started with Frozen Shoulder Treatment

- Book Sample /

- Health

Getting Started with Frozen Shoulder Treatment

This article was adapted from Dr. Karl Knopf‘s book Heal Your Frozen Shoulder

Frozen shoulder is a mysterious condition in which the connective tissues around the shoulder joint thicken and tighten, leading to loss of mobility. Basically, your shoulder “freezes” up. The technical definition of frozen shoulder is adhesive capsulitis, which is the medical term for stiffness and pain associated with limited range of movement in the shoulder. It most often occurs in just one shoulder but can occur in both.

Shoulder dysfunction is caused by many variables: falls, overuse, misuse, and even disuse after an injury. Injury to the soft tissue surrounding the shoulder joint may very well be prevented if you perform a gentle strengthening program of corrective exercises, but if you currently have a frozen shoulder you may already know this and now want to get better. The good news is that 90 percent of frozen shoulders can be rehabilitated. Patience and a regular schedule of gentle exercises are key.

The intent of Heal Your Frozen Shoulder is to offer you corrective exercises that you can do over a lifetime to prevent the condition from returning. Heal Your Frozen Shoulder will give a brief overview of shoulder anatomy, describe frozen shoulder dysfunction, and provide corrective and post-rehab exercises.

Heal Your Frozen Shoulder is not meant to be a replacement or a substitute for medical care or physical therapy. For the best chance of full recovery, all treatment plans should be designed with your individual characteristics in mind. With the supervision of a doctor and therapist, anyone can use Heal Your Frozen Shoulder to improve range of motion and strengthen the shoulder region. The information contained within Heal Your Frozen Shoulder has been gleaned from medical publications and therapy handbooks and represents the most current information about frozen shoulder. however, as with anything, as further clinical research is done, treatment plans may change.

Who Gets Shoulder Issues?

Statics show that, over a lifetime, more than 20 percent of the adult population has or will suffer from a shoulder joint dysfunction that affects daily activities. A shoulder dysfunction is no small problem; it can disable a person for a sustained period of time. The causes of shoulder problems are many and varied and can range from improper body mechanics, such as sitting incorrectly at the computer, or too many overhead movements. Who gets frozen shoulder issues?

• People who engage in repetitive overhead motions are more prone to shoulder pain and dysfunction.

• People who have prolonged immobilization of the joint due to pain or poor rehab.

• Women are more frequently affected than men.

• Those with a history of diabetes have a higher incidence than non-diabetics.

• Older people—incidence increases with age.

While age doesn’t cause shoulder problems, it unfortunately brings changes in joint structures and soft tissues of the shoulder joint. As we age, the soft tissues surrounding the shoulder girdle undergo some structural changes that often lead to the weakening of the supporting ligaments, tendons, and muscles.

Some experts in the field suggest that, by 50 years of age, most people have some internal shoulder structural changes. Often, tendinitis can manifest itself as a tendon degenerates with age and misuse. If simple chronic shoulder issues aren’t properly treated early, greater damage can occur—which is why early intervention and preventative maintenance are the key to complete shoulder health.

The occurrence of frozen shoulder is seen more frequently in people with a history of diabetes, or chronic inflammatory arthritis of the shoulder, or those who have had chest or breast surgery as well as a stroke. It’s very common to see a person who experiences shoulder pain try to protect the joint by not moving it. Any long-term immobility of the shoulder joint can put people at risk of developing a frozen shoulder.

Do I Have Shoulder Issues?

The onset of a shoulder problem often manifests slowly over time and is neglected until it affects the person’s range of motion or the pain is unbearable. Ironically, the natural response to stop using the shoulder when it hurts may actually contribute to a frozen shoulder.

Unfortunately, many people wait too long before going to the doctor about their shoulder problem, assuming it will just get better on its own. Research suggests that most people don’t go to the doctor until they’ve lost some level of range of motion. The current belief is that proactive steps such as medical care and gentle movement are the keys to preventing frozen shoulder syndrome.

If you suspect that you have a shoulder issue, get a diagnosis ASAP. An early intervention can keep a small issue from becoming a big one. Make an appointment with your primary care doctor, who’s usually the port of entry into the medical system. Your general doctor may then refer you to other health professionals.

Some signs that you may have a shoulder problem are:

• Difficulty moving a computer mouse around on the desk

• Pain when reaching upward, such as when putting groceries away on a high shelf

• hearing a shoulder “pop” after throwing a ball for your dog or after serving an ace in tennis

• Discomfort when reaching into your back pocket to grab your wallet or when pulling up a back zipper on a dress

What should I expect When Visiting the doctor?

When meeting with your health professional, explain to her all your functional limitations, such as difficulty or pain when:

• Putting on a coat

• Sleeping on your side

• Reaching behind you or to a high shelf

• Throwing a ball overhand

• Performing work duties

• Participating in recreational pursuits

Additionally, come prepared to share the type of work performed as well as your fitness routines, recreational pursuits, and any recent injuries. The more information you can provide will assist the health professional in developing a treatment plan. Don’t be discouraged sometimes in the case of a frozen shoulder the cause isn’t known.

Expect that the doctor will take a detailed health history as well as complete a comprehensive physical exam, possibly moving your arm through different motions while comparing it to your non-involved side. The doctor may order some x-rays to be taken of the shoulder to assist in making a diagnosis. You may receive a referral to a physical therapist, who might perform a biomechanical evaluation to look for any postural deviations and functional limitations. All these evaluations will assist in making a correct diagnosis and developing a proper treatment plan, which might include medications, physical therapy, and a home-care program.

Shoulder Anatomy

The shoulder, more accurately called the “shoulder girdle,” is a remarkable joint. It can gently toss an egg back and forth, rock a baby to sleep, hurl a baseball at 90 mph, and generate a 100-mph serve in tennis. The shoulder is much more than a single joint. This complex joint is where bones come together and are surrounded and supported by soft tissue, which includes ligaments, tendons, and bursas. Most experts maintain that the shoulder joint consists of the following bones: the humerus, scapular, and clavicle. Some experts even include the rib cage, thoracic, and cervical aspects of the spine.

An engineering marvel, the shoulder joint’s design allows for maximum flexibility and function in almost every conceivable direction. This mobility, however, is also why the shoulder girdle, a ball-and-socket joint, is so vulnerable to overuse and injuries, and one reason why it’s the most difficult and complicated joint in the body to rehabilitate.

The current philosophy in health care today is “knowledge is power.” To help you understand why certain treatment and exercise plans are beneficial to rehabilitating and preventing a frozen shoulder, here’s a basic overview of the shoulder anatomy and its kinesiology. Understanding your condition will help you follow through with the steps needed to fully recover.

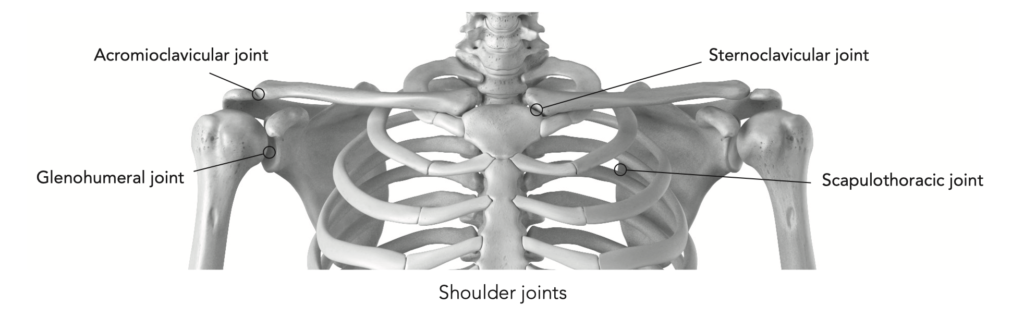

Shoulder Bones & Joints

The shoulder joint consists of a large ball and smaller socket. The basic structure is similar to a sideway-lying golf tee with a tennis ball next to it, held in place with a series of bands called ligaments and tendons. Ligaments attach bone to bone while tendons attach muscle to bone. This anatomical design, unfortunately, doesn’t provide a great deal of structural support. Generally, in the human body, extensive flexibility at a joint also means reduced stability. By comparison, the hip is also a ball-and-socket joint, but it’s a deep ball and socket, which provides a great deal of structural support but not much mobility.

The normal shoulder joint function allows for:

• Flexion and extension

• horizontal and lateral adduction and abduction

• Internal and external rotation

• Upward and downward scapular motion

The shoulder girdle is composed of four bones. The clavicle is commonly known as the collar bone. The scapula is also known as the shoulder blades, or wing/angel bones. The acromion is the part of the scapula that forms a bony roof above the rotator cuff, tendons, and bursa. The sternum is often referred to as the breast bone. The humerus is the upper bone of the arm.

Bones & Joints

Joints, where bones come together, are surrounded by soft tissue, which includes ligaments, tendons, and bursas.

There are several joints/articulations of the shoulder. The majority of the joint movement occurs in the glenohumeral joint; the other joints serve more as supporting structures. acromioclavicular (aC)—This joint is formed by the acromion and the clavicle. Mainly, it’s active with shrugging movements.

Glenohumeral (GH)—The combination of the upper arm bone and the outside area of the scapula makes up this joint. This joint is responsible for most of the movements of the shoulder. Shoulder dislocation always refers to this joint.

Sternoclavicular (SC)—This joint is composed of the clavicle and the sternum. This joint primarily operates during shrugs, although part of its function is to stabilize the shoulder girdle. Scapulothoracic (St)—This isn’t really a movable joint but serves as a base for muscles to be secured to.

Each of the four rotary cuff muscles originates on the scapula and their tendons attach to the top of the humerus, helping to form the joint capsule.

Ligaments & Tendons

The shoulder joint’s ligaments and tendons impart stability, but these bands can become lax through misuse and chronic overuse. Each type of fiber has a unique role to play and offers different abilities. Some shoulder experts call these elements the “passive system.” All this complexity allows the shoulder joint to be one of the most mobile joints of the body. This mobility, however, is also why the shoulder joint is so vulnerable to overuse and injuries, and one reason why it’s the most difficult and complicated joint in the body to rehabilitate.

Ligaments attach bone to bone while tendons attach muscle to bone. Ligaments are not just some simple set of guide wires; they twist and turn to provide stability along with providing neuromuscular feedback via the proprioceptive nervous system. Often with age these ligaments lose tensile strength, setting up a potential for injury. The ligaments of the shoulder region are the acromioclavicular ligament, also known as the AC joint ligament, and the coracoclavicular ligament.

The Joint Capsule

CARTILAGE

Cartilage is the gristle/pad between joints, providing cushion. The cartilage is designed to provide a smooth surface for joint bones to glide over. Often, with use, these once-smooth surfaces wear down. Once they break down, as seen in osteoarthritis, pain and inflammation occur.

BURSA

The sac surrounding the joint is called a bursa. A fluid-filled bursa is usually found between bones and tendons to help decrease friction during normal joint use. It provides lubrication to the joint. Many times, after frequent insults and impingements, the bursa becomes inflamed, causing pain that can lead to restricted movement.

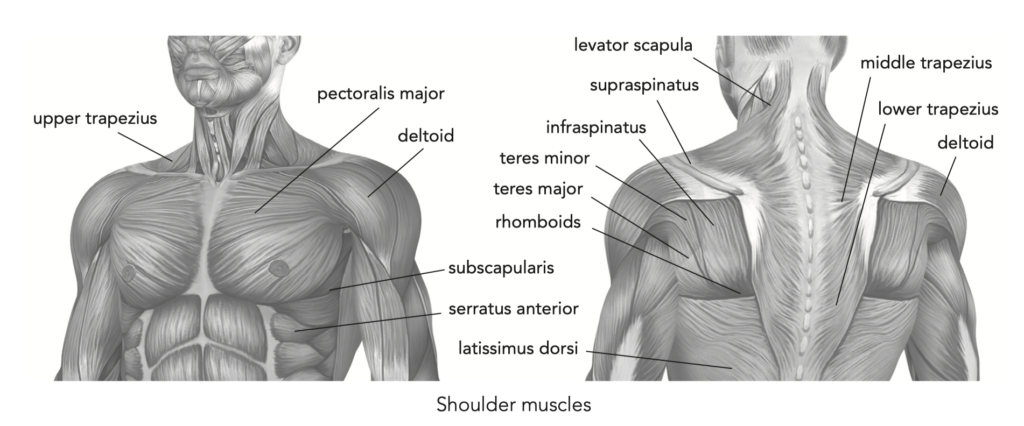

Muscles

Before we move on to the muscles of the shoulder, remember that muscles can do two things: contract or relax. Agonist muscles are responsible for contraction movements, while antagonist muscles produce an action opposite of the agonist. In addition, stabilizer muscles anchor or support a bone so the agonist can have a firm base from which to operate (the rotator cuff muscles are a good example of a stabilizer muscle).

The major muscles of the shoulder region are sometimes broken down into either static stabilizers (SS) or dynamic stabilizers (DS) of the joint. The muscles below serve to influence the motions available at the shoulder joint.

Static stabilizers:

• Supraspinatus abducts the arm (i.e., moves the arm away from the body).

• Infraspinatus rotates the arm laterally.

• Teres minor rotates the arm laterally.

• Teres major adducts the arm (i.e., brings the arm in to the body).

• Subscapularis internally rotates the arm. Dynamic stabilizers (prime movers):

• Latissimus dorsi extends and adducts the arm.

• Trapezius elevates and depresses the scapula.

• Pectoralis major and minor adduct the arm and pull the scapula downward.

• Coracobrachialis flexes and adducts the arm.

• Deltoid abducts and extends the arm.

• Levator scapula moves the neck laterally.

• Rhomboid major and minor stabilize the scapula.

• Serratus anterior stabilizes the scapula.

Other than trauma and repetitive chronic misuses, muscle imbalances, whether caused by work duties or recreational activities, are the prime culprit when it comes to shoulder injury. If one set of muscles gets too tight, the delicate balance of the space in the shoulder complex is upset, possibly throwing the alignment out of place. This is similar to the guide wires of a radio tower; if they’re too tight, they can cause misalignment. These misalignments set the stage for injury. When the alignment of the joint is proper, ideal range of motion is expected. Many times the cause of a shoulder problem can be traced back to misuse, overuse, disuse, or abuse of the shoulder joint and its supporting systems. Very often, postural deviations or muscle imbalances as a result of job duties or recreational activities can contribute to shoulder issues.

The muscles that are often implicated as being too tight and contributing to a shoulder imbalance are the:

• Trapezius (upper region)

• Levator scapula

• Sternocleidomastoid

• Internal rotators

• Pectoralis major and minor

• Latissimus dorsi The muscles commonly found to be too weak are:

• Trapezius (middle and lower region)

• Rhomboids

• Serratus anterior

• External rotators

Perhaps if we followed Joseph Pilates’ advice of strengthening what is weak and stretching what is tight, possibly some of our shoulder issues would’ve never occurred.

Heal Your Frozen Shoulder

A comprehensive at-home rehab, strengthening, and maintenance program for recovering from and preventing frozen shoulder. The cause of your frozen shoulder may be a mystery, but the way to fix it is no secret. Heal Your Frozen Shoulder guides you through the entire rehabilitation process, from understanding the problem to regaining full

Learn more