Ayahuasca and DMT: An Intro from The Psychedelic Handbook

- Book Sample /

- Wellness

Ayahuasca, DMT, Ketamine, psilocybin–more and more, these substances are the subject of mainstream conversation. From potential therapeutic benefits for depression and anxiety to increasing overall wellness, psychedelics hold incredible potential. But there is a lot of misinformation and distrust still out there.

Ayahuasca, DMT, Ketamine, psilocybin–more and more, these substances are the subject of mainstream conversation. From potential therapeutic benefits for depression and anxiety to increasing overall wellness, psychedelics hold incredible potential. But there is a lot of misinformation and distrust still out there.

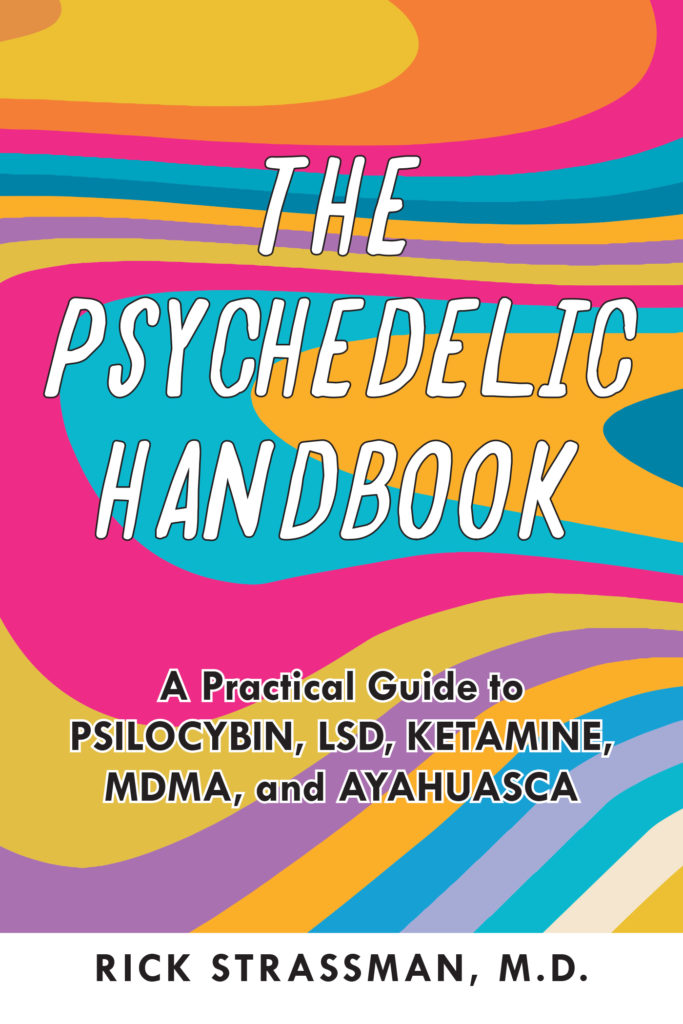

That’s why Dr. Rick Strassman wrote The Psychedelic Handbook: A Practical Guide to PSILOCYBIN, LSD, KETAMINE, MDMA, and DMT/AYAHUASCA. The following is a brief excerpt describing the history and use of DMT and ayahuasca.

Dr. Strassman’s book is available now for more in-depth history, research, and guidance on the world of psychedelics.

DMT and Ayahuasca

Dimethyltryptamine, or DMT, is the simplest of the classical tryptamine psychedelics, not much larger than blood sugar or glucose. It is of great significance because of its presence in the mammalian brain. In addition, the Latin American DMT-containing brew, ayahuasca, is increasingly popular throughout the world. This interest has led to a surge in “ayahuasca tourism” in Latin America, legal ayahuasca-using churches in the West, underground “wellness” centers, and academic research into its psychotherapeutic potential.

History and Botany of DMT and Ayahuasca

Indigenous Latin Americans have been using psychedelic snuffs and brews containing DMT for thousands of years. Ayahuasca is a combination of two plants. The most common DMT-containing plant is Psychotria viridis. As DMT is orally inactive, it requires inhibition of the enzyme that breaks it down in the gut—monoamine oxidase or MAO. By a remarkable feat of pharmacology, Indigenous peoples in Latin America discovered the efficacy of combining the DMT-containing plant with one that inhibits MAO—Banistereopsis caapi. Syrian Rue—Peganum harmala—which grows in North America, also contains the MAO-inhibiting compounds necessary for oral DMT activity. Even pharmaceutical MAO-inhibiting drugs that see use for depression are effective in inhibiting DMT breakdown in the gut, resulting in “pharmahuasca.” While DMT-containing and MAO-inhibiting plants usually form the basis of ayahuasca, sometimes the brew may not contain any DMT. Many other plants—for example, tobacco—play a role, depending on the intended effect.

Ayahuasca goes by several names depending on the setting of its use: for example, caapi, daime, hoasca, and vegetal. Ayahuasca is a Quechua word meaning “vine of the soul” or “vine of the dead.” This points to its ability to provide access to normally invisible and immaterial worlds.

Anthropologists and botanists from the West first learned of ayahuasca’s existence and properties in the mid-1800s, beginning with Richard Spruce. Richard Evans Schultes’ field studies in the 1950s reignited interest in it, especially within the nascent psychedelic subculture.

Richard Manske in Canada first synthesized DMT in the 1930s as one of a series of novel tryptamines, but he did not study it. Latin American and US chemists eventually isolated DMT from psychedelic plants. Stephen Szára, a Hungarian psychiatrist and chemist, unable to obtain LSD from Sandoz from behind the Iron Curtain, discovered DMT’s psychedelic properties in a series of self-experiments. Noticing no effect through increasingly large oral doses, he decided to inject it, and thus discovered its psychoactivity.

DMT remained a psychedelic niche drug for some time: short acting, intense, and active only after injection. Interest increased significantly, however, after its discovery in mammalian—including human—urine, spinal fluid, and blood.

The role of DMT in endogenous—that is, naturally occurring—psychoses was a major area of research during the first wave of human studies. Scientists sought to determine if DMT levels, formation, breakdown, or sensitivity differed between, say, schizophrenic patients and healthy subjects. Evidence supporting a role for endogenous DMT and naturally occurring psychoses was inconclusive by the time the CSA curtailed human psychedelic drug research. Despite calls for giving the DMT-psychosis theory a “decent burial” in the 1970s, this area remains of interest to scientists, especially in Europe.

The renewal of American clinical psychedelic drug research started with our five-year DMT project at the University of New Mexico that began in 1990.

Chemistry and Pharmacology

In plants and animals, tryptophan is the first step in DMT synthesis. Plants produce their own tryptophan—an amino acid—but mammals must ingest it through the diet. One enzyme converts tryptophan into tryptamine, and another adds two methyl groups to tryptamine, resulting in di-methyltryptamine (dimethyltryptamine).

For years, scientists believed the lungs made DMT, but recent data indicate brain synthesis with minimal or no lung production. The theory of pineal synthesis of DMT, which I proposed in my 2001 book, remains inconclusive. A 2013 study reported its presence in living rodent pineal gland, but a 2019 study suggested that the previously reported pineal DMT instead came from the brain.

More important than whether the pineal makes DMT are the data demonstrating that the mammalian brain makes this psychedelic in concentrations similar to those of well-known neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. This suggests the existence of a DMT neurotransmitter system. In addition, DMT levels increase in the dying rodent brain, especially in the visual cortex. This supports the idea that elevated levels of endogenous DMT contribute to the visual elements of the near-death state.

Laboratory synthesis of DMT is relatively simple, but the required chemicals are on the DEA “watch list.” Therefore, the most common way of obtaining DMT for non-research purposes is by extracting it from DMT-rich plant material, frequently from Mimosa hostilis root bark.

The pharmacology of DMT is like other classical compounds. The serotonin 1A and sigma-1 receptors also play a role. A non-psychedelic analog of DMT—iso-DMT—is psychoplastogenic. DET (diethyltryptamine) and DPT (dipropyltryptamine) are two short-acting tryptamines that saw use during the first wave of human research. While both are active by injection, they have the added advantage of being orally active, with a duration of approximately two hours.

The primary MAO-inhibiting substances in ayahuasca belong to the betacarboline family of compounds. These include harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine. These compounds by themselves possess psychoactive properties and likely contribute to the gastrointestinal side effects of the brew. However, their primary contribution is to allow DMT to become orally active. Taking oral DMT approximately twenty minutes after taking pure harmine or harmaline produces an orally active DMT experience.

Psychological tolerance to repeated frequent administration of DMT does not occur. We found no decrease in psychological effects after giving a full dose every thirty minutes four times in a morning. DMT does not exhibit cross-tolerance with other classical compounds, either. That is, an LSD- or psilocybin-tolerant person will still respond normally to a full dose of DMT.

Learn more about Dr. Strassman’s other book

Dose and Route of Administration

DMT is orally inactive and thus requires either smoking, snorting, or injecting. Smoking is the most common method, employing the freebase, which people vaporize and then inhale. DMT vape pens provide a less harsh smoking experience. When smoked or injected, effects begin within a couple of heartbeats, peak at two to ten minutes, and are barely noticeable at thirty to forty minutes. Ayahuasca effects begin at about thirty to sixty minutes, peak at two to three hours, and resolve over the next three to four hours. Vaporized DMT freebase is active at between 35–55 mg. People sometimes mistake DMT for 5-methoxy-DMT, which is ten times as potent; thus, one must make certain not to overdose on the latter compound believing it is the less potent DMT.

The amount of DMT in ayahuasca varies considerably depending on the specific brew. A low psychoactive dose of DMT in ayahuasca is about 30 mg, a medium dose 50 mg, and a high dose 70 mg and above. However, other studies have reported between 180–450 mg of DMT in a “dose.” In addition, ayahuasca may be more or less concentrated, meaning a small volume of liquid may contain more DMT than a larger volume of more dilute material. Since estimates vary so widely, it makes sense to begin with a small amount of ayahuasca if you are not familiar with its effects.

Effects and Side Effects of Ayahuasca

The first thing one notices after smoking or injecting DMT is a “rush,” a sense of inner tension and acceleration. Rapidly with smoked DMT, and more gradually with an adequate dose of ayahuasca, one loses awareness of the body and responsiveness to the outside world. However, as opposed to the “K-hole” of high-dose ketamine intoxication, if forced to move, one can. Once established, the DMT experience is highly visual with eyes open and especially when closed. Rapidly swirling, intensely saturated, and colored kaleidoscopic visual patterns may coalesce into more or less recognizable objects—for example, humanoid, insect-like, mechanical, or botanical “beings.” DMT seems to produce “contact” with beings more often than the other classical psychedelics. These “entities” are aware of us, and mutual interactions take place. They may be benign or malevolent, and they often communicate with us verbally—usually telepathically from “mind to mind” rather than hearing an audible voice.

Smoked DMT produces robust increases in blood pressure and heart rate, and those with heart disease should avoid this route of administration. Ayahuasca also increases blood pressure and heart rate, but not as powerfully. In addition, nausea from the brew may lead to decreased heart rate and blood pressure. Another name for ayahuasca is “the purge,” and vomiting and diarrhea are common even in those who use it regularly.

Studies of long-term ayahuasca users—mostly in the setting of ayahuasca religious organizations—provide reassuring data regarding long-term effects of regular use—three to five times per month for decades. General medical and psychiatric health and well-being are equal to or greater than those of matched controls. There is no evidence of brain damage; in fact, neuropsychological test scores are often better than those of matched controls. I have already mentioned a study that demonstrated increased thickness of certain parts of the cerebral cortex in long-term users, consistent with a psychoplastogenic effect.

Like psilocybin, ayahuasca produces rapid benefit in patients with depression and anxiety. DMT has begun seeing use as an antidepressant, and additional studies are determining its potential benefit in treatment of acute stroke and hastening functional recovery after a stroke.

Legality of DMT and Ayahuasca

Pure DMT is a Schedule I drug. However, the use of ayahuasca in the US by two Brazil-based churches is legal. The US Supreme Court ruled unanimously in 2006 to protect the religious use of ayahuasca for one of these churches, the UDV (In Portuguese: União do Vegetal—“The union of the plants.”). Several years later, federal courts similarly granted an exemption for ayahuasca use in another church, the Santo Daime (“Holy Daime.” In Portuguese, daime means “give me.”).

Disclaimers: Possessing or consuming a psychedelic may lead to arrest and criminal prosecution. It is very important for you to consult your own primary care and/or psychiatric provider before using any psychedelics and before decreasing or stopping any medications that you may be using if you wish to do so before taking a psychedelic. The use of psychedelics may result in negative psychological and/or medical health effects, and so does the discontinuation of medicines that you may be taking now if you wish to stop them before taking a psychedelic. Preliminary clinical research data suggest psychedelics have a role to play in treating a variety of mental health conditions, but none are yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration except for a proprietary brand of ketamine in those with cases of treatment-resistant depression who are currently taking an antidepressant. While people who microdose find the practice helpful, there are no scientific data supporting these claims.

The Psychedelic Handbook

Discover everything you need to know about psychedelics with this ultimate guide packed with information on popular psychoactive drugs like psilocybin, ketamine, MDMA, DMT and LSD—plus practical tips for microdosing and trip sitting—from bestselling author Dr. Rick Strassman. Entering the world of psychedelics can be daunting, and many

Learn more