Vagus Nerve Stimulation: A Beginner’s Guide

- Health

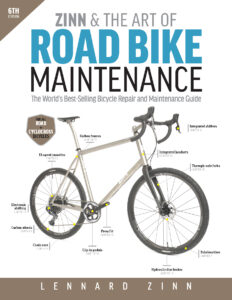

Your vagus nerve is the largest and most important nerve in your body. It carries messages to and from your brain, gut, heart and other major muscles and organs. However, common issues like inflammation, stress, or physical trauma can interfere with the nerve’s ability to function. Luckily, there are tons of quick-and-easy ways to exercise the nerve, strengthening its function and restoring your body to good health. Packed with easy-to-follow exercises and activities, Activate Your Vagus Nerve will show you how to unlock the power of the vagus nerve to heal your body and get back to a state of balance, all through vagus nerve stimulation.

What is the Vagus Nerve?

The vagus nerve (VN) originates in the brainstem—essentially the trunk of the brain that senses, processes, and regulates the vast majority of the automatic functions of the body. For the most part, we do not have to consciously think about these functions to make them happen. These functions are called autonomic and are regulated by your autonomic nervous system.

- Beating of the heart

- Blinking of eyelids

- Breath rate and depth

- Constriction and dilation of blood vessels

- Detoxification in the liver and kidneys

- Digestion in the digestive tract

- Opening and closing sweat glands

- Producing saliva and tears

- Pupil dilation and constriction in eyes

- Sexual arousal

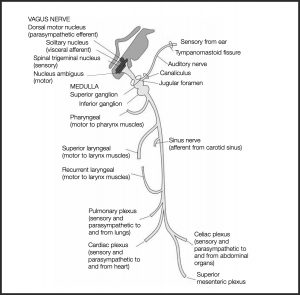

Inside the brainstem are various clusters of neuron cell bodies called nuclei. Here, neurons take in information from other cells throughout the body. These nuclei have different functions and are distinguished with Latin-derived names. Nuclei are like a router on a home internet network connection. Some information comes into the router through your cable connection or telephone line, the information is processed in the router, and other information is then sent out from the router to your computer, television, and any other electronics that are connected to your network.

There are two main types of neurons, and they send information in one of two directions. The first are afferent neurons, which receive information about what is taking place in and around the body. Afferent neurons take information from the body toward the brain, called afferent information. The second are called efferent neurons, which send out information with regulatory or motor effects (called efferent information) to various organs and structures throughout the body, so efferent information is carried from the brain, toward the body.

The vagus nerve is connected to four different nuclei within the brainstem. Eighty percent of the information transmitted by the VN is afferent information, meaning that the most common direction that information flows in the VN is from the organs of the body to the brain. The remaining 20 percent of the neurons in the VN have an efferent signal, from the brain to the body, leading to specific functions taking place in each cell and organ. It’s intriguing to learn that most medical students are shocked at the fact that only 20 percent of the VN’s function is efferent, as it has so many efferent effects on the organs—just imagine then the amount of information that this nerve relays back to the brain, more than four times as much as the information it relays away from it.

Like the wires of your home network connection, the bundles of neurons within your nerves send information along their length using electrical signals, which, upon reaching the end of the nerve, lead to the release of a chemical signal called a neurotransmitter. These neurotransmitters will bind to receptors on the receiving cells, leading to an effect in the cells at the end of the connection. The major neurotransmitter utilized by the VN is called acetylcholine (ACh for short), which has a major anti-inflammatory effect in the body.

Managing the inflammatory system is one of the most important functions of the VN; it is the major inflammatory control system in the body and has far-reaching effects on your personal state of health and disease. Many of the health conditions that my patients suffer from are due to high levels of inflammation in certain organs and systems, from the digestive tract to the liver and even the brain.

Inflammation is an important response within the body to keep us safe from bacterial and viral invaders, physical trauma, and other things that should optimally not enter the body. When inflammation levels are not kept in check and become chronic, the effects can be wide-ranging and lead to many different health conditions. Some common conditions correlated to high inflammation levels include:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Arthritis

- Asthma

- Cancer

- Crohn’s disease

- Diabetes

- Heart and cardiovascular disease

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)

- Ulcerative colitis

As well as any condition that ends in the suffix –itis Most of the organs affected in these conditions are innervated (or connected) by the VN. Thus, it is not just possible but highly likely that the VN is working suboptimally and not having its anti-inflammatory effect on these organs, leading to chronic inflammation and disease.

It’s important to remember that these conditions do not occur in isolation and if one of these conditions is present, another is likely to be taking place. The same signals are sent through the vagus nerve to and from nearly each internal organ, so if inflammation levels are not controlled in one organ, the same is likely occurring in other areas.

Exercises for Vagus Nerve Stimulation

Simple Breathing Exercise to Stimulate Your Vagus Nerve

The first and most effective way to positively affect your vagus nerve is to learn to breathe correctly. Simply put, rapid, shallow, chest breathing is a sign of stress, which activates the sympathetic branch, while slow, deep, belly breathing is a sign of rest, which activates the vagus nerve.

Breath is our one window into the autonomics.

—Dr. Jared Seigler

The vast majority of us have not learned to breathe correctly. In fact, we have subconsciously trained ourselves to forget the correct mechanics of breathing. If you haven’t yet completed the paradoxical breathing pattern test on page 128, I highly recommend doing it now. Correct breathing patterns are directly linked to autonomic nervous system function and altered breathing patterns tell the body that it is under stress.

This fact is even more amplified once you realize that the average person takes approximately 23,040 breaths per day.

When we want to learn the best, most efficient, and most effective way to breathe, we must look toward leaders and examples that live amongst us. Consider some of the greatest vocal and instrumental performers of our time. If you have ever attended a concert or opera, you have likely noticed that exceptional singers and instrumentalists can sing an entire set of songs without much of a break. In songs recorded by greats such as Frank Sinatra, Aretha Franklin, and Celine Dion, the artists rarely sound as though they are out of breath or unable to hold a note because they trained their breathing patterns. Opera singers are some of the most effective breathers on the planet; they have learned to control the function of their diaphragm while holding the vibration of their vocal muscles.

Another group to consider are high-performing professional athletes. These are the best of the best—those who do not crumble under pressure. Stars like Michael Jordan, Tom Brady, Cristiano Ronaldo, Tiger Woods, Wayne Gretzky, Nolan Ryan, Ken Griffey Jr., and Babe Ruth all had one thing in common—they were all able to control their stress levels by ensuring that their breath patterns stayed optimal while they were performing. To perform at such high levels, these performers trained themselves to remain calm under high-stress circumstances by using a slow, calm, and comfortable breathing pattern. You, too, can learn to create an optimal breathing pattern that can signal to your body that you are not under stress, thus allowing optimal signaling via the vagus nerve and parasympathetic nervous system.

Multiple research studies have shown that slow breathing exercises are highly effective in improving heart rate variability. One study showed that slowing your breath rate to six full breaths per minute for five minutes was effective in increasing HRV immediately. If this is individualized, the effect on HRV is even more effective. Determining the slow breath rate that is optimal and feels right for you individually will have the greatest positive effect on your HRV levels.

Here are simple steps to practice this exercise:

- Sit up straight without allowing your back to rest against anything.

- Exhale completely to remove all air from your lungs.

- Put your right hand on your chest and your left hand on your belly, just above your belly button.

- Take a deep breath in through your nose for five to seven seconds, allowing only your belly to rise (feeling only your left hand rising).

- Hold that breath for two to three seconds.

- Exhale through your mouth for six to eight seconds, allowing your belly to fall (feeling only your left hand falling).

- Hold your breath, without any air entering your lungs, for two to three seconds.

- Repeat steps 4 through 7 as many times as you feel comfortable or for a set period of time.

Take five minutes per day to practice deep belly breathing on your own and your body will thank you. For best results, perform this practice multiple times per day, especially during periods of stress. Even a single minute of concentrated focus on slow, deep breathing can have significant positive effects on your mood, stress levels, and overall health. Work to focus your attention on breathing in through your nose rather than your mouth to make this exercise even more effective when you are practicing it.

If you have already learned to practice this simple deep breathing exercise and are up for something a little more challenging and advanced, I recommend trying the Wim Hof breathing exercise. Wim Hof is a Dutch “daredevil” according to Google, however in learning his method, I now see him as a visionary. He is also known as the “Ice Man” as his training and methodology involves the use of breathing exercises and cold exposure as well as commitment to the practice.

Learn more exercises and techniques to boost vagus nerve stimulation with Activate Your Vagus Nerve.

Activate Your Vagus Nerve

Repair your vagus nerve and experience amazing health and wellness benefits Your vagus nerve is the largest and most important nerve in your body. It carries messages to and from your brain, gut, heart and other major muscles and organs. However, common issues like inflammation, stress, or physical trauma can interfere with the nerve’s

Learn more

Get the Ulysses Press Newsletter